More than 600,000 people die from hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) each year. Worldwide research on the disease needs to be intensified in both the medical and pharmaceutical fields, especially with a focus on providing help to areas where resources are limited.

Treatment approaches depend on the stage of the disease at diagnosis and on access to complex treatment regimens. However, advanced disease is not curable, and management of advanced disease is expensive and only marginally effective in increasing quality-adjusted life-years.

The delivery of health-care services for HCC can be improved by developing centers of excellence. Concentrating medical care in this way can lead to an increased level of expertise, so that resections are performed by surgeons who understand liver disease and the limitations of resection and other relevant procedures.

Promising new agents are beyond the reach of those who would benefit most: in low-resource countries, sorafenib is out of the question for general use. For example, “snapshot” cost indications of monthly pharmacy prices for sorafenib are: $7300 in China, $5400 in the USA, $5000 in Brazil, €3562 in France, and $1400 in Korea (source: N Engl J Med 2008;359:378–90; PMID 18650519).

From a global perspective, therefore, the most urgent task is to prevent the occurrence of HCC. The only effective strategy is primary prevention of viral hepatitis, and in most countries this is already in place in the form of hepatitis B vaccination of newborns. Prevention of alcohol abuse and preventing the spread of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and metabolic syndrome are also relevant. Another important task is to prevent aflatoxin formation through proper care of crops and food storage. The next best approach is to increase awareness among the health-care community in order to promote surveillance of patients who are at risk and achieve earlier diagnosis and resection or ablation of small lesions.

Global prevalence and incidence

HCC is the sixth most common malignancy worldwide. It is the fifth most common malignant disease in men and the eighth most common in women. It is the third most common cause of death from cancer, after lung and stomach cancer.

HCC is the most common malignant disease in several regions of Africa and Asia. At least 300,000 of the 600,000 deaths worldwide occur in China alone, and the majority of the other 300,000 deaths occur in resource-challenged countries in sub-Saharan Africa. These devastating figures are most likely due to:

- Failure to recognize those at risk (with hepatitis B and/or C)

- High prevalence of risk factors in the population

- Lack of medical expertise and facilities for early diagnosis

- Lack of effective treatment after diagnosis

Other important factors include poor compliance, with inadequate or absent attendance in surveillance programs and thus late presentation of patients with large tumors; low awareness of the benefits of HCC treatment and ways of preventing underlying liver disease; and a negative opinion among some physicians about screening. In Japan, the United States, Latin America, and Europe, hepatitis C is the major cause of HCC. The incidence of HCC is 2–8% per year in patients with chronic hepatitis C and established cirrhosis. In Japan, the mortality from HCC has more than tripled since the mid-1970s. HCV infection is responsible for 75–80% of cases and hepatitis B virus (HBV) for 10–15% of cases. HCV-related HCC has been linked to blood transfusions in the 1950s and 1960s, intravenous drug use, and the reuse of syringes and needles. In many (but not all) countries, the spread of HCV is declining, but due to migration the disease burden has not changed.

In Asia, Africa, and in some eastern European countries, chronic hepatitis B is the prime cause of HCC, far outweighing the impact of chronic hepatitis C (Fig. 1). There are 300 million people infected with HBV, 120 million of whom are Chinese. In China and Africa, hepatitis B is the major cause of HCC; approximately 75% of HCC patients have hepatitis B.

Fig. 1 The worldwide geographic distribution of chronic hepatitis B virus infection

(source: Centers for Disease Control, 2006)

HCC risk factors

HCC is associated with liver disease independently of the specific cause of the disease:

- • Infectious: chronic hepatitis B or C.

- • Nutritional and toxic: alcohol, obesity (nonalcoholic fatty liver disease), aflatoxin (co-factor with HBV), tobacco.

- • Genetic: tyrosinosis, hemochromatosis (iron overload). However, iron overload as a cause per se and as a result of dietary intake (due to cooking in iron pots) is a subject of controversy.

- • α1-Antitrypsin deficiency.

- • Immunologic: autoimmune chronic active hepatitis, primary biliary cirrhosis.

The major risk factors for HCC are:

- Chronic hepatitis B or C virus infection.

- Alcoholic cirrhosis.

- Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

- Diabetes (metabolic syndrome is the likely risk process).

- Cirrhosis by itself, of whatever cause.

- In Europe, North America, and Japan, HCC occurs mainly in patients with established cirrhosis.

The risk of developing HCC in patients infected with HBV increases with:

- The viral load

- Male sex

- Older age

- The presence of cirrhosis

- Exposure to aflatoxins

- Location in sub-Saharan Africa, where patients develop HCC at a younger age

The risk of developing HCC in patients infected with HCV and cirrhosis increases in combination with:

- Concurrent alcohol abuse

- Obesity/insulin resistance

- Previous or concurrent infection with HBV

Primary care

Physical findings:

- If the tumor is small: often without symptoms

— No physical signs may be found at all

— Signs related to the chronic liver disease and/or underlying cirrhosis

- In more advanced cases:

— Palpable mass in the upper abdomen, or a hard, irregular liver surface

— Tenderness in the upper right abdominal quadrant

— Splenomegaly, ascites, jaundice (also symptoms of cirrhosis)

— Hepatic arterial bruit (heard over the tumor)

Signs that should raise a suspicion of HCC in patients with previously compensated cirrhosis:

- Rapid deterioration of liver function

- New-onset (or refractory) ascites

- Acute intra-abdominal bleeding

- Increased jaundice

- Weight loss and fever

- New-onset encephalopathy

- Variceal bleeding

Patients with late-stage HCC may present with:

- Right upper quadrant abdominal pain

- Symptoms and signs of underlying cirrhosis

- Weakness

- Abdominal swelling

- Nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms

- Jaundice

- Loss of appetite

- Weight loss

- Anorexia

Laboratory findings:

- Usually nonspecific

- Signs of cirrhosis:

— Thrombocytopenia

— Hypoalbuminemia

— Hyperbilirubinemia

— Coagulopathy

- Electrolyte disturbances

- Liver enzymes abnormal, but nonspecific

- Elevated alpha fetoprotein (AFP; requires definitions of levels and appropriate setting)

- Elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP)

Follow-up to assess the patient after therapy—to be performed every 3–6 months:

- Physical examination

- Laboratory blood tests

- Computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and ultrasonography

Referring for a specialist evaluation may help in:

- Confirming the diagnosis (and excluding possible alternatives—e.g., liver diseases).

- Determining the extent of hepatic involvement and (remaining) liver function.

- Excluding extrahepatic disease.

- Choosing the best therapeutic option, including palliative care. If expert centers are within reach, it is generally recommended that HCC patients should be referred there, where care and options are optimally applied with all the expertise required from different areas of knowledge.

Diagnosis

Initial patient evaluation:

- Complete history

- Full physical examination

- Initial laboratory tests:

— Complete blood count

— Serum glucose

— Renal function and serum electrolytes

— Alpha fetoprotein

— Albumin

—Prothrombin time

—Alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), bilirubin

- Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and anti-HCV (if not already known)

- Chest x-ray and/or CT scan

Ascitic fluid cytology may also be considered, despite its low sensitivity—it is simple and practicable in Africa.

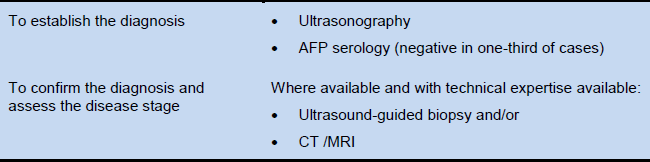

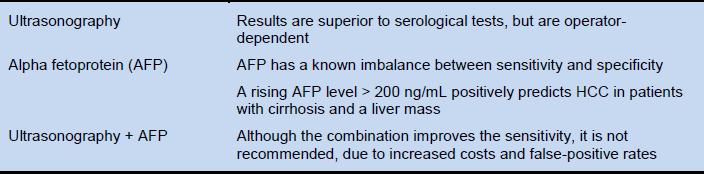

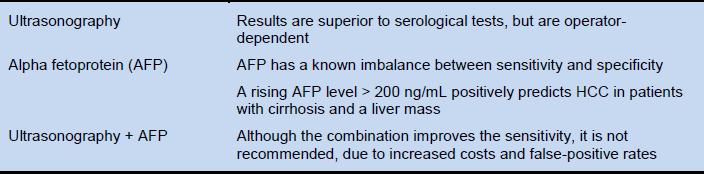

Diagnostic tests (Table 1). Sufficient to establish a diagnosis of HCC is a combined finding of: the classic appearance on one of the imaging modalities—i.e., a large and/or multifocal hepatic mass with arterial hypervascularity; and elevated serum AFP, against a background of chronic (generally asymptomatic), generally cirrhotic-stage liver disease.

Table 1 Tests used to diagnose hepatocellular carcinoma

AFP, alpha fetoprotein; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Ultrasound imaging, CT, or MRI. Radiology and/or biopsy are the definitive diagnostic tools. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound may produce false-positive findings for HCC in patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. AFP is an adjunctive diagnostic tool. A persistent AFP level of more than 400 ng/mL or a rapid increase in the AFP level may be a useful diagnostic criterion. In patients with lower AFP levels when radiology is not available, the diagnosis of HCC can only be made by clinical judgment. Even if options for treating HCC are absent or very limited, AFP testing and ultrasound imaging may be available.

Cautionary notes

- It is important to distinguish the use of AFP testing as a screening tool from its use as a diagnostic tool. Although it is considered to be a useful and feasible screening tool in China, others disagree. Its performance as a diagnostic tool is better. A positive AFP test (above 400 ng/mL, for example, can be considered diagnostic, but an AFP that is negative or below the predetermined cut-off point does not exclude HCC, since up to 40% of HCCs will never produce AFP. However, 90% of black African patients have raised AFP levels that are above the diagnostic level of 500 ng/mL in 70% of patients. However, this in turn may reflect the late presentation of these patients. In Western patients, AFP testing is less useful.

- Increased AFP and a mass are diagnostic of malignancy, but it is not possible to distinguish between HCC and cholangiocarcinoma. The incidence of cholangiocarcinoma is increasing, and cirrhosis is a risk factor. If the radiographic findings are conclusive, therefore, the diagnosis is certain; but if radiology is not conclusive, a biopsy is recommended in order to confirm the diagnosis.

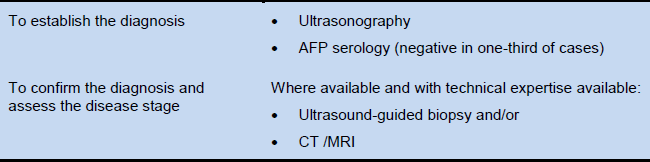

Cascades—a resource-sensitive approach

A “cascade” is a hierarchical set of diagnostic, therapeutic, and management options for dealing with risk and disease, ranked by the resources locally available.

A gold-standard approach is feasible in regions and countries where liver transplantation is available for the treatment of HCC. Elsewhere, resection and/or local ablation are available, but not liver transplantation. What is it still possible to do in the various settings in which transplantation or resection and/or local ablation are available?

To answer this question, this guideline is structured on the basis of resource-sensitive cascades: for minimal-resource and medium-resource areas, the guideline discusses primary and secondary prevention, patient evaluation, and treatment options. For high-resource regions and countries, the guideline published by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) should be consulted.

- Minimal-resource regions are defined as those in which hardly any treatment options are available. The focus is on prevention and symptomatic treatment. At best, resection or local ablation may be available in some areas.

- Defining the criteria for referral to a specialist is a complex matter. As patients with advanced cases (and these are the majority of cases in resource-challenged countries) have no treatment options except supportive care, referral is generally futile. Only patients with early cases can benefit (imaging technology is required to identify early cases) and should be referred to specialists.

- All recommendations should focus on primary prevention and on the treatment of viral hepatitis and cirrhosis.

Primary HCC prevention

Particularly when potentially curative treatment is unavailable, primary prevention is very important in reducing the risk of HCC (Table 2).

- The vaccination prevention strategy against viral hepatitis (HBV) should be carried out worldwide, and it has been implemented in 152 countries so far. It is supported by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) such as the Gates Foundation and the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI).

— Vaccination costs less than a dollar in Nigeria, and the vaccine is free for babies in public hospitals and in immunization centers though the National Program on Immunization (NPI) there.

— Pakistan runs the World Health Organization’s “Expanded Program of Immunization” (EPI), with free immunization for all newborns.

- Antiviral therapy should be recommended if needed:

— In many countries, the problem with antiviral therapy is management (drug resistance), compliance, and education.

— Costs may also be a problem, although several medications are reported to be relatively inexpensive. One year of lamivudine treatment costs $165 in Sudan; adefovir is inexpensive in India and China; and entecavir in China costs $5/day compared with $22/day in developed countries.

- Health education work on viral hepatitis should emphasize the ways in which it is possible for disease to spread in relation to local practices involving blood–blood contact, such as circumcision, scarification, tribal marks, and tattoos; in relation to the care of open sores and marks following multiple-use tooth extraction equipment; and in connection with the reuse of needles (or multiple-dose vials).

Table 2 Options for primary prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma

HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBIG, hepatitis B immune globulin.

* Deciding which individuals infected with hepatitis B or C require treatment is a complex issue that goes beyond the scope of this document.

Secondary HCC prevention—surveillance

Screening should be encouraged in regions in which it is possible to offer curative treatment for HCC. There is little point in carrying out mass screening of a population if the resources for further investigation and treatment are lacking. Screening should only be undertaken if at least one of these management options is available: liver transplantation, resection, transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), or ablation techniques. Treatment with acetic acid (vinegar) is used in some places.

One of the starting-points for screening is to identify asymptomatic patients with HCC. If patients have cancer symptoms at diagnosis, the outcome is not good and treatment is not likely to be cost-effective.

Treatment options

Appropriate treatment options that may or may not be beyond the scope of local medical facilities include:

- Partial liver resection

- Percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI) or radiofrequency ablation (RFA)

- Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE)

Traditional chemotherapy has no place in the management of HCC. Patients should be offered symptomatic treatment when it is needed and possible.

- Medium-resource regions are defined as those in which both resection and ablation are available for the treatment of HCC, but transplantation is not an option.

- In addition to primary HCC prevention (as discussed under “Minimal resources” above), detailed recommendations can be provided on surveillance, diagnosis, and treatment.

- The delivery of health-care services for HCC can be improved by developing centers of excellence—concentrating medical care can lead to an increased level of expertise, so that resections are performed by surgeons who understand liver disease and the limitations of each treatment modality.

Secondary HCC prevention—surveillance

When resection and/or local ablation are available for the treatment of HCC, there should be an emphasis on surveillance.

Primary prevention—i.e., hepatitis B vaccination of youngsters—is optimal in reducing the risk of HCC. Early diagnosis and treatment are essential for improving survival, but preventing recurrent HCC is still a major challenge.

HCC surveillance may improve early detection of the disease. Generally, treatment options are broader when HCC is detected at an earlier stage.

- Finding early-stage disease is a prerequisite for improved prognosis.

- Screening should be encouraged in regions in which it is possible to offer curative treatment for HCC.

- The risk factors for HCC are well known, and this allows cost-effective surveillance.

Screening for early detection of HCC is recommended for the groups of high-risk patients listed in Table 3.

Table 3 Criteria for hepatocellular carcinoma screening

Surveillance involves establishing screening tests, screening intervals, diagnostic criteria, and recall procedures (Table 4).

- Depending on the clinical condition and the available resources, an ultrasound screening interval of 6–12 months is recommended.

- In advanced cases and in patients with cirrhosis, ultrasound screening should be done every 4–6 months.

- Patient education is an essential prerequisite.

Table 4 Surveillance techniques

See the “Cautionary notes” under “Diagnosis” above.

Tertiary HCC prevention—recurrence

Recurrent HCC may result from multicentric carcinogenesis or inadequate initial treatment. Prevention of HCC recurrence requires early diagnosis and complete removal of primary HCC lesions.

Currently, there is no proof of the efficacy of tertiary prevention of HCC with any agent, including chemotherapy, HBV and HCV therapy, or interferon (IFN).

- There are no safe and effective chemotherapeutic agents available yet to prevent recurrence of HCC.

- Molecular-targeted drugs appear to show promising clinical activity, but the median survival is not satisfactory and these agents are very costly.

- Anti-HBV oral nucleoside/nucleotide analogues are required for patients with ongoing active chronic hepatitis B with HCC as a complication and who are in Child–Pugh class A or B.

Evaluation

The management of HCC is changing. In the developed countries, HCC patients are increasingly being evaluated and managed in specialized centers by multidisciplinary pathologists.

The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system takes into account variables related to tumor stage, liver function, physical status, and cancer-related symptoms, and links these with treatment options and life expectancy. On the basis of the BCLC staging system, patients may classified as having:

- Early HCC: single nodule or three nodules ≤ 3 cm. These patients may benefit from curative therapies.

- Intermediate HCC: multinodular. These patients may benefit from chemoembolization.

- Advanced HCC: multinodular with portal invasion. These patients may benefit from palliative treatments; new agents may be considered.

- End-stage HCC: very poor life expectancy; symptomatic treatment.

After a diagnosis of HCC has been confirmed, liver function is one of the main factors in the treatment selection process; performance status and comorbid conditions need to be established.

Important aspects in assessing liver function are:

- Child–Pugh classification:

— Bilirubin (total)

— Serum albumin

— Prothrombin international normalized ratio (INR)

— Ascites

— Hepatic encephalopathy

- Optional: hepatic venous pressure gradient. A test result > 10 mmHg would confirm clinically relevant portal hypertension, which is important when surgical resection is planned.

Treatment options

Treatment options largely depend on liver function, tumor size, and the presence or absence of metastatic lesions or vascular invasion. In most cases, curative treatments such as resection, radiofrequency ablation, or liver transplantation are not feasible, limiting the options to palliation. Screening of at-risk populations is therefore the only way of detecting tumors at a stage at which they are capable of being treated. Most of the treatment options are expensive and/or require specialized centers. Resection and local ablation are the treatment options most likely to be used in patients with HCC identified during surveillance in developing countries.

Both resection and ablation can allow a cure in small tumors.

- Partial liver resection:

— Possibly a curative approach for HCC.

— Only a few of the patients qualify for this option, due to advanced disease stage and/or reduced liver function.

— Relapse can be either due to residual tumor that was incompletely treated the first time round, or a true recurrence—i.e., a second independent tumor arising in a liver that is prone to develop malignancy.

- Percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI) or radiofrequency ablation (RFA):

— These are safe and effective when resection is not an option, or when the patient is awaiting transplantation.

— PEI is universally available, but requires at least ultrasound .

— PEI and RFA are equally effective for tumors < 2 cm.

— RFA is more effective than alcohol injection in tumors > 3 cm.

— The necrotic effect of RFA is more predictable in all tumor sizes.

- Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE). This is the standard of care for patients with good liver function and disease that is not amenable to surgery or ablation, but who have no extrahepatic dissemination, no vascular invasion, and no cancer symptoms.

Table 5 presents a recent description of treatments, their benefits in HCC, and levels of evidence, developed by an AASLD expert panel.

Table 5 American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) expert panel description of treatments, benefits, and levels of evidence in hepatocellular carcinoma

Source: Llovet JM, Di Bisceglie AM, Bruix J, et al. Design and endpoints of clinical trials in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:698–711.

* Classification of evidence adapted from National Cancer Institute: www.cancer.gov. Study design: randomized controlled trial, meta-analysis = 1 (double-blinded 1i; nonblinded 1ii). Nonrandomized controlled trials = 2. Case series = 3 (population-based 3i; non–population-based, consecutive 3ii; non–population-based, nonconsecutive 3iii). End points: survival (A), cause-specific mortality (B), quality of life (C). Indirect surrogates (D): disease-free survival (Di), progression-free survival (Dii), tumor response (Diii).

† Although sorafenib may be unavailable for treatment in low-resource regions and countries, and perhaps even medium-resource ones, it has a proven impact that is as good as, or better than, many systemic cancer treatment options for other cancers.

- Patients with Child–Pugh class C cirrhosis should be offered symptomatic treatment only.

- More recent experimental methods, such as brachytherapy and selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT), are available in specialized centers.