Comprehensive Cancer Care Requires a Dedicated Gastroenterologist

Vol. 27, Issue 1 (March 2022)

|

Toufic Kachaamy, MD, FASGE, AGAF

Enterprise Program Leader, Interventional Programs

Medical Director of Gastroenterology - Phoenix

Cancer Treatment Centers of America® (CTCA)

|

Cancer care is evolving rapidly. This evolution is in part due to new and innovative treatments such as targeted therapy and immunotherapy. These treatments have transformed many cancers from a grave diagnosis to chronic, survivable diseases. In certain instances, these treatments have changed metastatic cancer from a fatal disease to a curable (or manageable) illness. The medical-surgical sub-specialties involved in cancer treatment have also advanced significantly.

Historically, the cancer care team has consisted of a medical oncologist, a radiation oncologist, and a surgical oncologist. In the modern era, additional specialties such as palliative care, pain management, minimally invasive/robotic surgery, and interventional gastroenterology and pulmonology often play an important role in the provision of comprehensive cancer care. For example, in gastroenterology, therapeutic endoscopists now are an integral part of the multidisciplinary cancer team and many cancer centers now have full-time gastroenterologists (interventional endoscopists) as part their team.

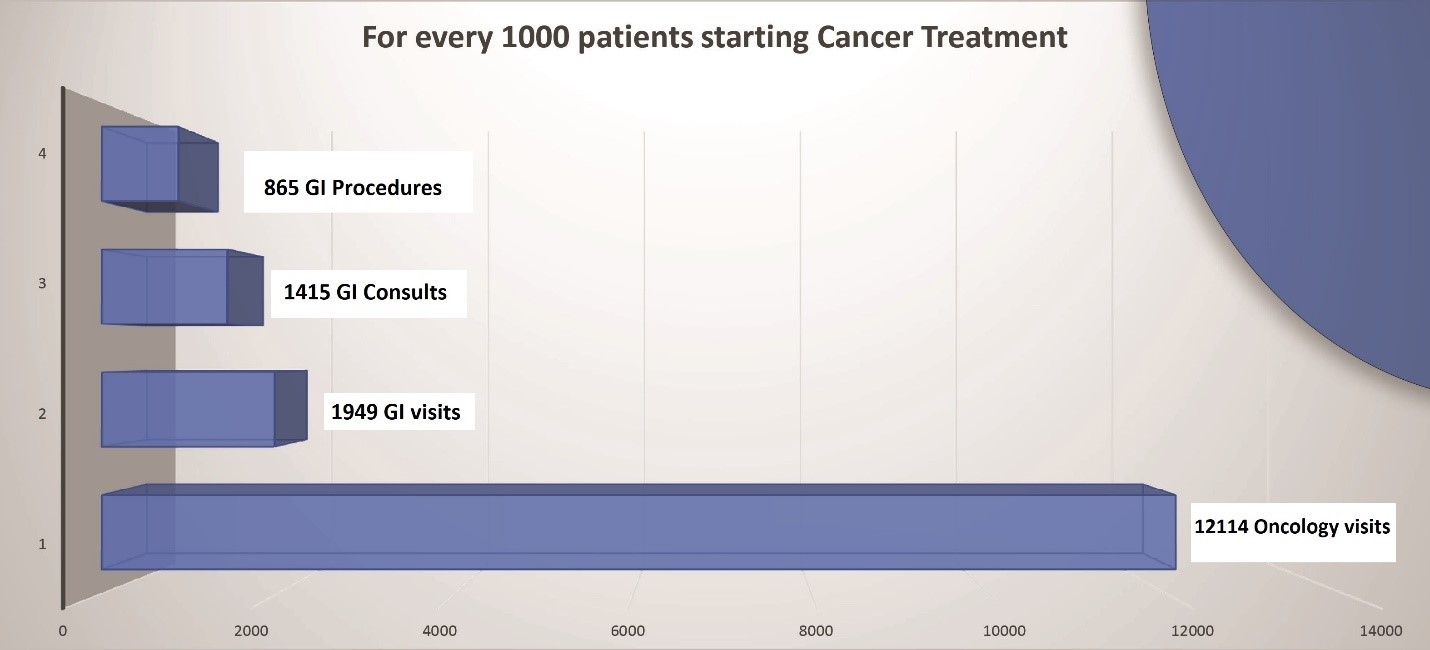

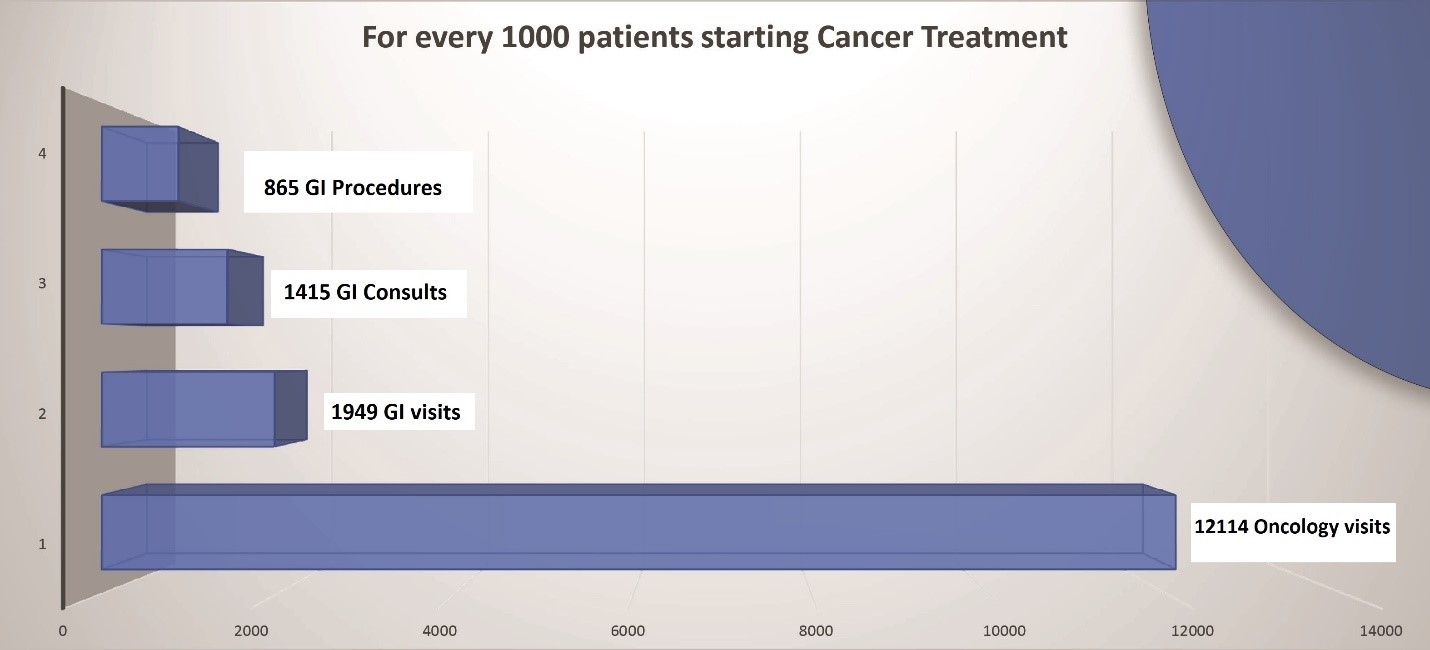

This article serves to outline how gastroenterology’s role has moved beyond cancer screening and diagnosis into cancer staging, resection, ablation, palliation, and high-risk surveillance in survivorship. The typical relative volume of gastroenterology patient encounters at a cancer center is shown in figure 1. For every 1000 patients receiving active cancer treatment, there is around 2000 GI clinic encounters and 860 procedures. These can serve as an estimate for GI resources and staffing based on the patient volume in a cancer center aiming to provide comprehensive care including gastroenterology services.

Figure 1: GI case volume per 1000 patients receiving active cancer treatment (CTCA Phoenix data)

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), a not-for-profit alliance of 31 leading cancer centers devoted to patient care, research, and education, has updated guidelines on cancer screening, diagnosis, management, supportive care, and surveillance. These guidelines are available on NCCN.org. While most gastroenterologists are familiar with gastrointestinal society guidelines, those involved in managing cancer patients need to become familiar with the NCCN guidelines as they represent state-of-the-art, evidence-based recommendations for comprehensive cancer care.

The gastroenterologist involved in cancer care must understand the terminology used in oncology. For example, palliative therapy may seem to imply therapy that is aimed at relieving symptoms; but, in the oncology world, it refers to therapy aimed at prolonging survival and is not curative in intent, regardless of the impact on symptoms.

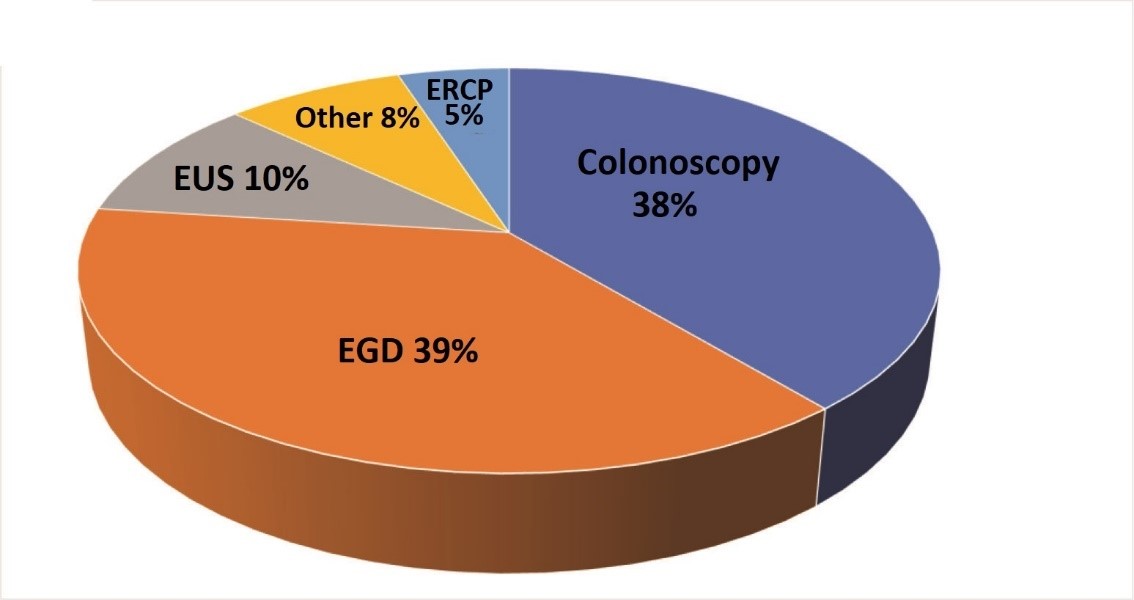

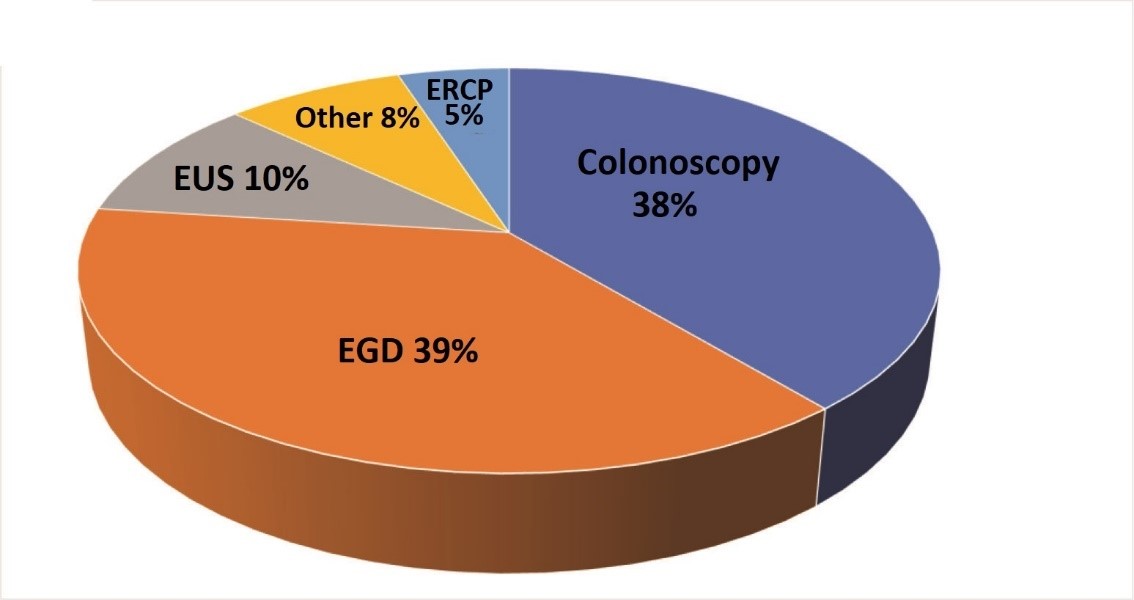

In a cancer center, the gastroenterologists’ practice includes cancer screening, cancer diagnosis, staging and restaging, acquiring tissue for genomic testing, and cancer resection/ablation/palliation. In addition, managing immunotherapy and targeted therapy induced gastrointestinal toxicity is increasingly being encountered. Gastroenterologists are important members of a team providing support to the cancer patient throughout their journey and provide valuable input when end of life decisions are made. The key aspects of a gastroenterologist’s role in a GI cancer center are highlighted in this review. The typical percentage of different types of GI procedures performed at a comprehensive cancer care center is shown in figure 2.

Figure 2: GI procedures distribution at a cancer center (CTCA Phoenix Data)

Cancer screening

While a significant part of the general gastroenterology practice focuses on colon cancer screening, in the cancer population, screening often involves high-risk patients with an increased risk of multiple malignancies, requiring a more extensive understanding of genetic disorders and the associated risks. Furthermore, cancer patients are exposed to certain treatments which increase their future cancer risk. For example, abdominal radiation is known to increase the risk of colon cancer and thus will affect the screening interval for such patients. The American Cancer Society recommends consideration for colorectal cancer screening every five years in patients who have a prior history of abdominal radiation.1 A common scenario is when a patient with cancer also has a family history of cancer. After this patient undergoes genetic counselling and testing, the individual may be identified to have a certain mutation which warrants specific high risk screening and surveillance. For example, patients with certain genetic mutations such as STK11 and CDKN2A are recommended to undergo pancreatic cancer screening starting at the age of 30 or 40 respectively while patients with ATM, BRCA, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, EPCAM, PALB2 or TP53 mutations are recommended to undergo screening if they have family history of pancreatic cancer with screening starting at the age of 50 or 10 years before the age of diagnosis in affected family members. Screening for pancreatic cancer is recommended with yearly MRI or EUS, ideally at high volume centers.2

Cancer staging and restaging

A therapeutic endoscopist plays an important role in (endoluminally) classifying cancers into esophageal, gastric, or gastroesophageal based on the location of the tumor epicenter and in determining its stage, typically using EUS. The gastroenterologist also plays a key role in restaging after treatment. It is important to be familiar with classification of treatment response, especially complete clinical response (CCR). Complete clinical response is defined as complete tumor regression after initial treatment, often based on physical exam, radiologic and endoscopic (sometimes with biopsy) criteria. In rectal cancer, complete clinical response requires complete resolution of the tumor on endoscopy with residual white scar or minimal superficial ulceration and negative biopsies. This has significant implications on the patient’s management plan. For example, based on the most recent NCCN guidelines, it is now acceptable practice to allow patients to opt into a “watch and wait approach” for complete clinical response after neoadjuvant treatment for distal rectal cancer.3 This requires an intensive surveillance program including repeat endoscopy for the first two years post treatment.4

GI bleeding in cancer patients

GI bleeding in cancer patients is common and presents its unique set of challenges. It can be from traditional non cancer sources of bleeding such as peptic ulcer disease, or from the cancer itself as in gastric or colonic cancer or metastasis to the gastrointestinal tract. Bleeding in cancer patients can also be caused by cancer treatment such as from systemic therapy with antiangiogenic agents (Bevacizumab) such as or radiation induced vascular angioectasia as in radiation proctitis. Hemobilia can occur in cancer patients with liver metastasis or biliary stents and is often difficult to diagnose and manage. A high index of suspicion for hemobilia is needed especially in patients presenting with melena and worsening in their liver function tests with negative endoluminal examinations.

The gastroenterologist plays a critical role in the diagnosis and management of bleeding in this population. In patients who have brisk bleeding, or patients with cancers in areas that are known to be near vascular structures and in patients with prior endoluminal stents in locations that predispose to major vessel involvement (eg esophageal stents eroding into the thoracic aorta) we typically obtain a scan CT with no oral contrast. This sometimes identifies the source of bleeding or help classify it into arterial or venous in etiology.

The management of bleeding in cancer patients is often multidisciplinary with the gastroenterologist coordinating the care with interventional radiology and surgery. The options available to the gastroenterologist to manage luminal GI bleeding are increasing and include injectables such as cyanoacrylate, mechanical (endoclips), thermal such as Argon Plasma coagulation and bipolar cautery and the more recently introduced hemostatic powders and gels. While initial endoscopic hemostasis has been reported to be high, rebleeding often occurs. Multidisciplinary management is likely to be the most successful with surgery, interventional radiology, radiation oncology and systemic therapy being other means available to try to achieve durable hemostasis. Unfortunately, in some cases, severe uncontrolled bleeding may end up being a terminal event.

Cancer diagnosis

The gastroenterologist performing endoscopy plays a central role in the diagnosis of gastrointestinal cancers. The gastroenterologist is consulted to diagnose suspected cancer based on imaging abnormalities such as GI tract wall thickening or a mass seen on a CT scan. Cancer recurrence can sometimes occur years after the original cancer has been treated (such as renal cell cancer recurrence presenting as a mass in the pancreas).5 Luminal endoscopy with biopsy and Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS) with fine needle aspiration (FNA) are now well-established modalities to allow safe and efficient tissue acquisition to confirm a diagnosis of GI cancer. With the ability to consistently acquire high quality “core” biopsies at EUS, molecular profiling of tumors and subtyping of lymphomas is possible using minimally invasive tissue acquisition techniques.

Genomic testing

Determining the genetic profile of the tumor can allow the patients to access targeted therapies. These are therapies based on the genetic profile of the cancer. This testing requires a larger amount of tissue than is typically needed for a typical histologic diagnosis. It is important to communicate with the oncologist about the amount of tissue needed prior to the procedure, especially for certain malignancies such as pancreatic cancer, as obtaining more tissue can involve significantly more passes into the tumor and the use of larger (or core) needles, impacting procedure preparation, time and potentially nature of anesthesia/sedation.

Jorje Medina, Advanced Endoscopy Technician (Left) and Toufic Kachaamy, Therapeutic Endoscopist (Center) conduct therapeutic upper with esophageal cancer ablation. Nurse, Elaine Jewett (Right) monitors the abdomen for any excessive distention from liquid nitrogen expansion.

Cancer resection

Endoscopic resection (ER) represents a major advance in the management of pre-neoplastic and neoplastic lesions. ER provides both staging (diagnostic) and therapeutic advantages and is now routinely performed for eligible lesions in the esophagus, stomach, small bowel and colon. The devices and techniques for ER have also rapidly evolved over the past two decades, allowing the therapeutic endoscopist involved with GI cancer care to provide minimally invasive management options to these patients. In most cases, these novel interventions obviate the need for surgery and its associated morbidity. Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), submucosal dissection (ESD) and full thickness resection (EFTR) are now well-established endoscopic procedures with excellent outcomes and minimal morbidity. When invasive malignancy is found after endoscopic resection, multidisciplinary review and NCCN guideline based consensus recommendations are invoked, thus ensuring that the patient has the best possible outcome in every case.

Cancer ablation

Various modalities for cancer ablation are now available to the endoscopist. EUS-guided radiofrequency ablation (RFA) can be used to treat small symptomatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors.6 Endobiliary RFA is increasingly being used to prolong biliary stent patency.7 Cryoablation is being used for esophageal cancer dysphagia palliation and for treatment of residual esophageal cancer after chemoradiation in patients who are not candidates for esophagectomy.8 An interesting phenomenon worth mentioning when we discuss cancer ablation is the abscopal effect of the treatment. The abscopal effect occurs when a systemic tumor response is seen after a local form of therapy such as radiation or endoscopic ablation. While it is still being investigated, it has become a topic of interest since the emergence of immunotherapy. What is especially interesting is the potential for synergistic effect of local therapy and immunotherapy. This field is still in its infancy but is potentially very promising.9

Immunotherapy or targeted therapy-induced gastrointestinal toxicity

Immunotherapy has revolutionized cancer care, leading to cures in certain conditions previously thought incurable. However, it may be associated with significant side effects especially affecting the GI tract. The common adverse events of immunotherapy include colitis and hepatitis. The gastroenterologist needs to become familiar with the diagnostic criteria, assessment of disease severity, the indications for endoscopy in this setting and management of these immunotherapy related complications. Interdisciplinary communication and collaboration is critical in such cases to ensure the best outcome.

A multidisciplinary discussion with Toufic Kachaamy, Therapeutic Endoscopist (Left), Saba Radhi, GI Oncologist (Center) and Krista Gomez, Therapeutic Endoscopy Nurse Practitioner (Right), about a patient who underwent positron emission tomography (PET) scan and Endoscopic Ultrasound (EUS findings).

Supportive care

The NCCN guidelines recommend the initiation of supportive care at the time of cancer diagnosis. Of the ten most common symptoms that cancer patients experience, half are related to the GI tract. These include anorexia and malnutrition, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, and malignant bowel obstruction. The gastroenterologist plays an important role in the diagnosis and management of these symptoms. Several diagnostic tests, medications, and procedural interventions are available to help manage these patients. For example, patients with gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) from tumor or radiation strictures can be successfully managed with endoscopic enteral (luminal) stenting or EUS-guided gastrojejunostomy (EUS-GJ).

End-of-life care

The gastroenterologist taking care of cancer patients needs to become knowledgeable about the prognosis of different GI cancers and the signs and symptoms that are associated with end of life. Procedures should be avoided at the end of the life unless they are palliative and provide significant comfort to the patient. The gastroenterologist needs to become comfortable with being able to empathetically communicate difficult news to the patients and their families and help the patient manage their care at the end of life. It is not uncommon for a patient seen by a gastroenterologist to have irreversible jaundice and for the gastroenterologist to be the first provider faced with the patient’s difficult questions. This discussion should ideally involve the oncology team and specialists from palliative care as well.

Conclusion

Gastroenterologists have assumed increasingly integral roles as part of the multidisciplinary GI cancer care team. This evolution is in part due to the rapid advancements in medical and endoscopic interventions we can offer to the cancer patient, as well as our improved appreciation and recognition of the value of a multidisciplinary approach to cancer care.

Gastroenterology training programs will need to consider incorporating education and awareness around the skill sets required to be a successful stakeholder in GI cancer focused programs of the future. Continuing education programs, including those at national and international meetings, will benefit from specific programming dedicated to this rapidly evolving sub-specialty of gastroenterology. One such effort is at a CME event in Scottsdale, Arizona, focusing on the various aspects of the multidisciplinary GI cancer care team, including a focus on the endoscopic intervention options for the patient with GI cancer. Further growth of the GI cancer-focused gastroenterologist sub-specialty is expected, will add value to the multidisciplinary team, and will benefit our patients immensely.

REFERENCES:

1. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/acs-recommendations.html

2. NCCN guidelines: Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast, Ovarian, and Pancreatic. Version 1.2022. August 2021

3. NCCN guidelines: Rectal cancer. Version 2.2021-September 2021

4. López-Campos F, Martín-Martín M, Fornell-Pérez R, et al. Watch and wait approach in rectal cancer: Current controversies and future directions. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26(29):4218-4239.

5. Ballarin R, Spaggiari M, Cautero N, et al. Pancreatic metastases from renal cell carcinoma: The state of the art. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(43):4747-4756.

6. Jonica ER, Wagh MS. Endoscopic treatment of symptomatic insulinoma with a new EUS-guided radiofrequency ablation device. VideoGIE. 2020;5(10):483-485. Published 2020 Jun 27.

7. Alis H, Sengoz C, Gonenc M, et al. Endobiliary radiofrequency ablation for malignant biliary obstruction. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2013 Aug;12(4):423-7

8. Kachaamy T, Prakash R, Kundranda M et al. Liquid nitrogen spray cryotherapy for dysphagia palliation in patients with inoperable esophageal cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018 Sep;88(3):447-455.

9. Ngwa, W., Irabor, O., Schoenfeld, J. et al. Using immunotherapy to boost the abscopal effect. Nat Rev Cancer 18, 313–322 (2018).

10. Heller SJ, Tokar JL, Nguyen MT, Haluszka O, Weinberg DS. Management of bleeding GI tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010 Oct;72(4):817-24.