1. Introduction

Dysphagia refers either to the difficulty someone may have with the initial phases of a swallow (usually described as “oropharyngeal dysphagia”) or to the sensation that foods and or liquids are somehow being obstructed in their passage from the mouth to the stomach (usually described as “esophageal dysphagia”). Dysphagia is thus the perception that there is an impediment to the normal passage of swallowed material. Food impaction [1] is a special symptom that can occur intermittently in these patients.

Oropharyngeal swallowing is a process that is governed by the swallowing center in the medulla, and in the mid-esophagus and distal esophagus by a largely autonomous peristaltic reflex coordinated by the enteric nervous system. Table 1 lists the physiological mechanisms involved in these various phases.

Table 1 The physiological mechanisms involved in the stages of swallowing, by phase

A key decision is whether the dysphagia is oropharyngeal or esophageal. This distinction can be made confidently on the basis of a very careful history, which provides an accurate assessment of the type of dysphagia (oropharyngeal vs. esophageal) in about 80–85% of cases [2]. More precise localization is not reliable. Key features to consider in the medical history (specifics are discussed below) are:

- Location

- Types of foods and/or liquids

- Progressive or intermittent

- Duration of symptoms

Although the conditions can frequently occur together, it is also important to exclude odynophagia (painful swallowing). Finally, a symptom-based differential diagnosis should exclude globus pharyngeus (a “lump in the throat” sensation), chest pressure, dyspnea, and phagophobia (fear of swallowing).

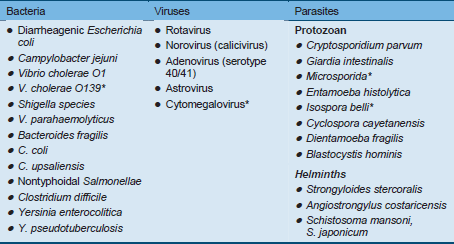

1.1 Causes of dysphagia

When one is trying to establish the etiology of dysphagia, it is useful to follow the same classification adopted for symptom assessment—that is, to make a distinction between causes that mostly affect the pharynx and proximal esophagus (oropharyngeal or “high” dysphagia), on the one hand, and causes that mostly affect the esophageal body and esophagogastric junction (esophageal or “low” dysphagia), on the other. However, it is true that many disorders overlap and can produce both oropharyngeal and esophageal dysphagia. Thorough history-taking, including medication use, is very important, since drugs may be involved in the pathogenesis of dysphagia.

Oropharyngeal dysphagia

In young patients, oropharyngeal dysphagia is most often caused by muscle diseases, webs, or rings. In older people, it is usually caused by central nervous system disorders, including stroke, Parkinson disease, and dementia. Normal aging may cause mild (rarely symptomatic [3]) esophageal motility abnormalities. Dysphagia in the elderly patient should not be attributed automatically to the normal aging process.

Generally, it is useful to try to make a distinction between mechanical problems and neuromuscular motility disturbances, as shown below.

Mechanical and obstructive causes:

- Infections (e.g., retropharyngeal abscesses)

- Thyromegaly

- Lymphadenopathy

- Zenker diverticulum

- Reduced muscle compliance (myositis, fibrosis, cricopharyngeal bar)

- Eosinophilic esophagitis

- Head and neck malignancies and the consequences (e.g., hard fibrotic strictures) of surgical and/or radiotherapeutic interventions on these tumors

- Cervical osteophytes

- Oropharyngeal malignancies and neoplasms (rare)

Neuromuscular disturbances:

- Central nervous system diseases such as stroke, Parkinson disease, cranial nerve palsy, or bulbar palsy (e.g., multiple sclerosis, motor neuron disease), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- Contractile disturbances such as myasthenia gravis, oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy, and others

Within 3 days of stroke, 42–67% of patients present with oropharyngeal dysphagia—making stroke the leading cause of dysphagia. Among these patients, 50% aspirate and one-third develop pneumonia that requires treatment [4]. The severity of the dysphagia tends to be associated with the severity of the stroke. Dysphagia screening in stroke patients is critical in order to prevent adverse outcomes related to aspiration and inadequate hydration/nutrition [5].

Up to 50% of Parkinson patients show some symptoms consistent with oropharyngeal dysphagia, and up to 95% are found to have abnormalities on video esophagography [6,7]. Clinically significant dysphagia may occur early in Parkinson disease, but it is more usual in the later stages.

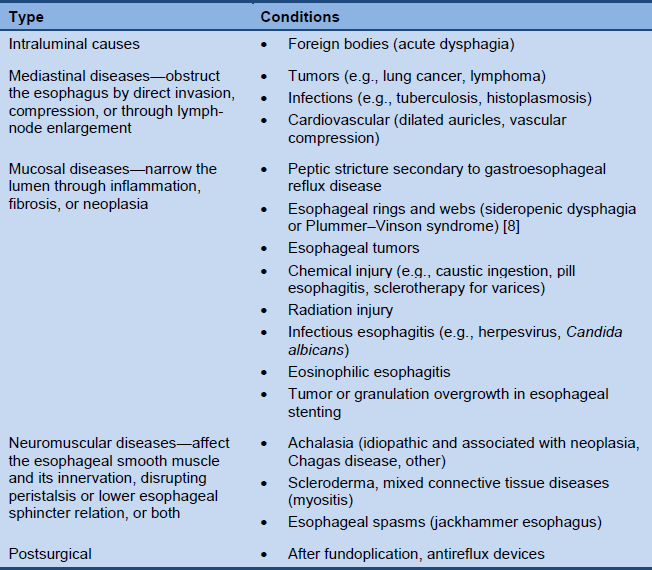

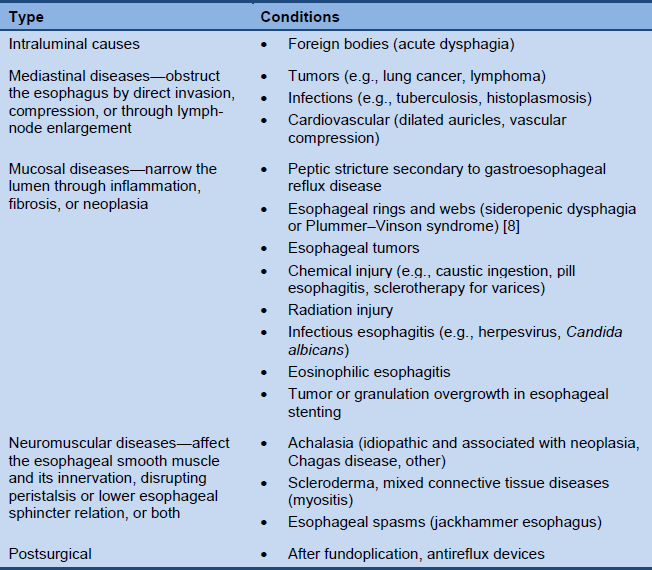

Esophageal dysphagia

Table 2 Most common causes of esophageal dysphagia

1.2 WGO cascades—global guidelines

Cascades—a resource-sensitive approach

A gold standard approach is only feasible if the full range of diagnostic tests and medical treatment options are available. Such resources for the diagnosis and management of dysphagia may not be sufficiently available in every country. The World Gastroenterology Organisation (WGO) guidelines provide a resource-sensitive approach in the form of diagnostic and treatment cascades.

A WGO cascade is a hierarchical set of diagnostic, therapeutic, and management options for dealing with risk and disease, ranked by the resources available.

Other publicly available guidelines

1.3 Disease burden and epidemiology

Dysphagia is a common problem. One in 17 people will develop some form of dysphagia in their lifetime. A 2011 study in the United Kingdom reported a prevalence rate of 11% for dysphagia in the general community [9]. The condition affects 40–70% of patients with stroke, 60–80% of patients with neurodegenerative diseases, up to 13% of adults aged 65 and older and > 51% of institutionalized elderly patients [10,11], as well as 60–75% of patients who undergo radiotherapy for head and neck cancer.

The disease burden of dysphagia is clearly described in a 2008 congressional resolution in the United States [12], which notes that:

- Dysphagia affects as many as 15 million Americans; all Americans over 60 will experience dysphagia at some point.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has estimated that 1 million people annually are diagnosed with dysphagia in the United States.

- The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has estimated that 60,000 Americans die annually from complications associated with dysphagia.

- Complications due to dysphagia increase health-care costs as a result of hospital readmissions, emergency room visits, extended hospital stays, the necessity for long-term institutional care, and the need for expensive respiratory and nutritional support.

- Including the money spent in hospitals, the total cost of dysphagia to the healthcare system is well over $1 billion annually.

- Dysphagia is a vastly underreported condition and is not widely understood by the general public.

Epidemiological data are difficult to provide on a global basis, since the prevalence of most diseases that may cause dysphagia tends to differ between regions and continents. Only approximations are therefore possible at the global level. Prevalence rates also vary depending on the patients’ age, and it should also be remembered that the range of disorders associated with childhood dysphagia differs from that in older age groups. In younger patients, dysphagia often involves accident-related head and neck injuries, as well as cancers of the throat and mouth. Dysphagia generally occurs in all age groups, but its prevalence increases with age.

Tumor prevalence differs in various countries. In the United States and Europe, for instance, adenocarcinoma is the most common type of esophageal cancer, whereas in India and China it is squamous cell carcinoma. Similarly, corrosive strictures of the esophagus (with individuals consuming corrosive agents with suicidal intent) and tuberculosis can also be important aspects in non-Western settings.

Regional notes

- North America/USA:

- Rates of reflux-induced stricture have been decreasing in the United States since proton-pump inhibitors became widely available [13].

- Eosinophilic esophagitis is increasingly being recognized as a major cause of dysphagia both in children and adults [13].

- Esophageal cancer is increasing in incidence, although the absolute numbers of patients diagnosed with esophageal cancer in the Unites States continues to be small.

- With the growing population of elderly patients in the United States, compression from cervical osteophytes, stroke, and other neurologic disorders are becoming even more important causes of dysphagia than they were in the past.

- The widespread use of ablative treatments for Barrett’s esophagus (radiofrequency ablation, photodynamic therapy, and endoscopic mucosal resection) is likely to lead to a new group of patients with strictures caused by endotherapy.

- Europe/Western countries:

- Whereas gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and peptic strictures are decreasing as causes of esophageal dysphagia, adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and eosinophilic esophagitis are increasing [14–16].

- Asia [17,18]:

- Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, achalasia, and surgery-related strictures are common reasons for dysphagia with esophageal causes. The prevalence of GERD appears to be increasing, but in comparison with Western countries, GERD is still less prevalent in Asia. Post-stroke dysphagia is quite common in Asia, and improvements in health care are gradually promoting the required early recognition and treatment.

- Latin America:

- Chagas disease is highly prevalent in some parts of Latin America. Chagasic achalasia and megaesophagus may develop and lead to malnutrition. Some features of Chagas achalasia differ from those of idiopathic achalasia. Lower esophageal sphincter pressure tends to be in the low range, apparently because both excitatory and inhibitory control mechanisms are damaged. However, the medical and surgical treatments are similar [19].

- Africa:

- In Africa, post-stroke dysphagia treatment may not be optimal due to insufficient resources or poor management of the resources that are available. Lack of qualified and knowledgeable health-care professionals may further account for the less than optimal services. There is also a lack of dedicated stroke units and instrumentation—particularly the imaging facilities needed for the gold standard of modified barium swallow assessments [20].

2. Clinical diagnosis

An accurate history covering the key diagnostic elements is useful and can often establish a diagnosis with certainty. It is important to carefully establish the location of the perceived swallowing problem: oropharyngeal vs. esophageal dysphagia.

2.1 Oropharyngeal dysphagia

Clinical history

Oropharyngeal dysphagia can also be called “high” dysphagia, referring to oral or pharyngeal locations. Patients have difficulty in initiating a swallow, and they usually identify the cervical area as the area presenting a problem.

In neurological patients, oropharyngeal dysphagia is a highly prevalent comorbid condition associated with adverse health outcomes including dehydration, malnutrition, pneumonia, and death. Impaired swallowing can cause increased anxiety and fear, which may lead to patients avoiding oral intake—resulting in malnutrition, depression, and isolation.

Frequent accompanying symptoms:

- Difficulty initiating a swallow, repetitive swallowing

- Nasal regurgitation

- Coughing

- Nasal speech

- Drooling

- Diminished cough reflex

- Choking (n.b.: laryngeal penetration and aspiration may occur without concurrent choking or coughing)

- Dysarthria and diplopia (may accompany neurologic conditions that cause oropharyngeal dysphagia)

- Halitosis in patients with a large, residue-containing Zenker diverticulum or in patients with advanced achalasia or long-term obstruction, with luminal accumulation of decomposing residue

- Recurrent pneumonia

Precise diagnosis is possible when there is a definite neurological condition accompanying the oropharyngeal dysphagia, such as:

- Hemiparesis following an earlier cerebrovascular accident

- Ptosis of the eyelids and fatigability, suggesting myasthenia gravis

- Stiffness, tremors, and dysautonomia, suggesting Parkinson disease

- Other neurological diseases, including cervical dystonia and compression of the cranial nerves, such as hyperostosis or Arnold–Chiari deformity (hindbrain herniations)

- Specific deficits of the cranial nerves involved in swallowing may also help pinpoint the origin of the oropharyngeal disturbance, establishing a diagnosis

Testing

Tests for evaluating dysphagia can be chosen depending on the patient’s characteristics, the severity of the problem, and the available expertise. Stroke patients should be screened for dysphagia within the first 24 hours after the stroke and before oral intake, as this leads to a threefold reduction in the risk of complications resulting from dysphagia. Patients with persistent weight loss and recurrent chest infections should be urgently reviewed [21].

A bedside swallow evaluation protocol has been developed by the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA); a template is available at http://www.speakingofspeech.info/medical/BedsideSwallowingEval.pdf. This inexpensive bedside tool provides a detailed and structured approach to the mechanisms of oropharyngeal dysphagia and its management, and it may be useful in areas with constrained resources.

Major tests for evaluating oropharyngeal dysphagia are:

- Video fluoroscopy, also known as the “modified barium swallow”

- This is the gold standard for evaluating oropharyngeal dysphagia [22–24].

- Swallowing is recorded on video during fluoroscopy, providing details of the patient’s swallowing mechanics.

- It may also help predict the risk of aspiration pneumonia [25].

- Video-fluoroscopic techniques can be viewed at slower speeds or frame by frame and can also be transmitted via the Internet, facilitating interpretative readings at remote sites [26].

- Upper endoscopy

- Nasoendoscopy is the gold standard for evaluating structural causes of dysphagia [22–24]—e.g., lesions in the oropharynx—and inspection of pooled secretions or food material.

- This is not a sensitive means of detecting abnormal swallowing function.

- It fails to identify aspiration in 20–40% of cases when followed up with video fluoroscopy, due to the absence of a cough reflex

- Fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES)

- FEES is a modified endoscopic approach that involves visualizing the laryngeal and pharyngeal structures through a transnasal flexible fiberoptic endoscope while food and liquid boluses are given to the patient.

- Pharyngoesophageal high-resolution manometry

- This is a quantitative evaluation of the pressure and timing of pharyngeal contraction and upper esophageal relaxation.

- It can be used in conjunction with video fluoroscopy to allow a better appreciation of the movement and pressures involved.

- It may have some value in patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia despite a negative conventional barium study.

- It may be useful when surgical myotomy is being considered.

- Automated impedance manometry (AIM) [27]

- This is a combination of impedance and high-resolution manometry.

- Pressure-flow variables derived from automated analysis of combined manometric/impedance measurements provide valuable diagnostic information.

- When they are combined to provide a score on the swallow risk index (SRI), these measurements are a robust predictor of aspiration.

- Water swallow test

- This is inexpensive and is a potentially useful basic screening test alongside the evidence obtained from the clinical history and physical examination.

- It involves the patient drinking 150 mL of water from a glass as quickly as possible, with the examiner recording the time taken and number of swallows. The speed of swallowing and the average volume per swallow can be calculated from these data. It is reported to have a predictive sensitivity of > 95% for identifying the presence of dysphagia, and it may be complemented by a “food test” using a small amount of pudding placed on the dorsum of the tongue [28].

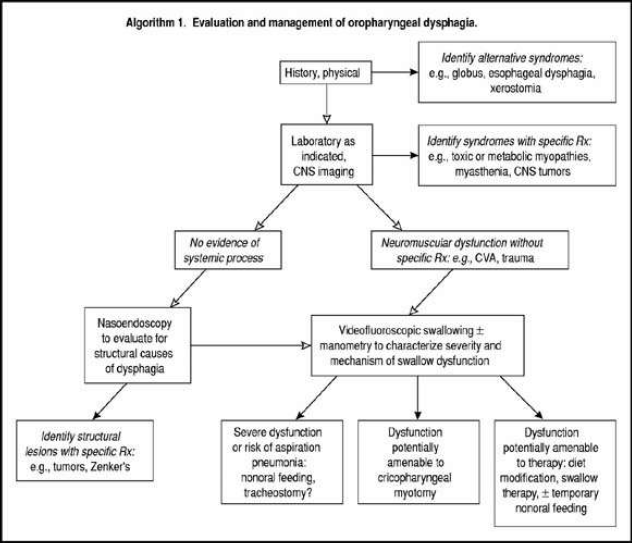

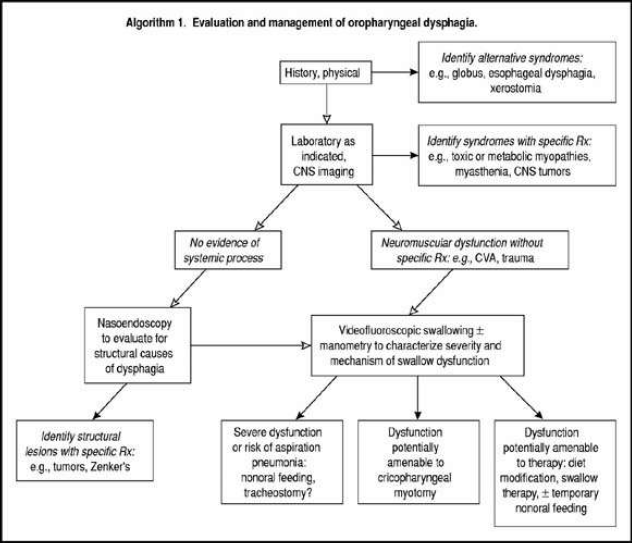

The algorithm shown in Fig. 1 provides an indication of more sophisticated tests and procedures that are needed in order to pursue a diagnostic investigation leading to specific therapies.

Fig. 1 Evaluation and management of oropharyngeal dysphagia

2.2 Esophageal dysphagia

Differential diagnosis

The most common conditions associated with esophageal dysphagia are:

- Peptic stricture—occurs in up to 10% of GERD patients [29,30], but the incidence decreases with proton-pump inhibitor use

- Esophageal neoplasia—including cardia neoplasia and pseudoachalasia

- Esophageal webs and rings

- Achalasia, including other primary and secondary esophageal motility disorders

- Scleroderma

- Spastic motility disorders

- Functional dysphagia

- Radiation injury

Rare causes:

- Lymphocytic esophagitis

- Cardiovascular abnormalities

- Esophageal Crohn involvement

- Caustic injury

Clinical history

Esophageal dysphagia can also be called “low” dysphagia, referring to a probable location in the distal esophagus—although it should be noted that some patients with forms of esophageal dysphagia such as achalasia may perceive it as being located in the cervical region, mimicking oropharyngeal dysphagia.

- Dysphagia that occurs equally with solids and liquids often involves an esophageal motility problem. This suspicion is reinforced when intermittent dysphagia for solids and liquids is associated with chest pain.

- Dysphagia that occurs only with solids but never with liquids suggests the possibility of mechanical obstruction, with luminal stenosis to a diameter of < 15 mm. If the dysphagia is progressive, peptic stricture or carcinoma should be considered in particular. It is also worth noting that patients with peptic strictures usually have a long history of heartburn and regurgitation, but no weight loss. Conversely, patients with esophageal cancer tend to be older men with marked weight loss.

- In case of intermittent dysphagia with food impaction, especially in young men, eosinophilic esophagitis should be suspected.

The physical examination of patients with esophageal dysphagia is usually of limited value, although cervical/supraclavicular lymphadenopathy may be palpable in patients with esophageal cancer. Some patients with scleroderma and secondary peptic strictures may also present with CREST syndrome (calcinosis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal involvement, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia).

Halitosis is a very nonspecific sign that may suggest advanced achalasia or longterm obstruction, with accumulation of slowly decomposing residues in the esophageal lumen.

The clinical history is the cornerstone of evaluation and should be considered first. A major concern with esophageal dysphagia is to exclude malignancy. The patient’s history may provide clues. Malignancy is likely if there is:

- A short duration – less than 4 months

- Disease progression

- Dysphagia more for solids than for liquids

- Weight loss

On the other hand, achalasia is more likely if:

- There is dysphagia for both solids and liquids. Dysphagia for liquids strongly suggests the diagnosis.

- There is passive nocturnal regurgitation of mucus or food.

- There is a problem that has existed for several months or years.

- The patient takes additional measures to promote the passage of food, such as drinking or changing body position.

Eosinophilic esophagitis is more likely if there is:

- Intermittent dysphagia associated with occasional food impaction.

Testing

The medical history is the basis for initial testing. Patients usually require early referral, since most will need an endoscopy. The algorithm shown in Fig. 2 outlines management decision-making on whether endoscopy or a barium swallow should be the initial test employed.

- Endoscopic evaluation:

- A video endoscope (fiberoptic endoscopes have largely been replaced by electronic or video endoscopes) is passed through the mouth into the stomach, with detailed visualization of the upper gastrointestinal tract.

- If available, high-resolution video endoscopy can be used to detect subtle changes, such as the typical whitish islands in eosinophilic esophagitis.

- Introducing the endoscope into the gastric cavity is very important in order to exclude pseudoachalasia due to a tumor of the esophagogastric junction.

- Endoscopy makes it possible to obtain tissue samples and carry out therapeutic interventions.

- Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is useful in some cases of outlet obstruction.

- Barium contrast esophagram (barium swallow):

- Barium esophagrams taken with the patient supine and upright can outline irregularities in the esophageal lumen and identify most cases of obstruction, webs, and rings.

- A barium examination of the oropharynx and esophagus during swallowing is the most useful initial test in patients with a history or clinical features suggesting a proximal esophageal lesion. In expert hands, this may be a more sensitive and safer test than upper endoscopy.

- It can also be helpful for detecting achalasia and diffuse esophageal spasm, although these conditions are more definitively diagnosed using manometry.

- It is useful to include a barium tablet to identify subtle strictures. A barium swallow may also be helpful in dysphagic patients with negative endoscopic findings if the tablet is added.

- A full-column radiographic evaluation [31] is helpful if a subtle mechanical impediment is suspected despite a negative upper endoscopic evaluation.

- A timed barium esophagram is very useful for evaluating achalasia before and after treatment.

- Esophageal manometry:

- This diagnostic method is based on recording pressure in the esophageal lumen using either solid-state or perfusion techniques.

- Manometry is indicated when an esophageal cause of dysphagia is suspected after an inconclusive barium swallow and endoscopy, and following adequate antireflux therapy, when healing of the esophagitis has been confirmed endoscopically.

- The three main causes of dysphagia that can be diagnosed using esophageal manometry are achalasia, scleroderma, and esophageal spasm.

- Esophageal high-resolution manometry (HRM) with esophageal pressure topography (EPT):

- Is used to evaluate esophageal motility disorders.

- Is based on simultaneous pressure readings with catheters with up to 36 sensors distributed longitudinally and radially for readings within sphincters and in the esophageal body, with a three-dimensional plotting format for depicting the study results (EPT).

- The Chicago Classification (CC) diagnostic algorithmic scheme allows hierarchical categorization of esophageal motility disorders. CC has clarified the diagnosis of achalasia and of distal esophageal spasm.

- Radionuclide esophageal transit scintigraphy:

- The patient swallows a radiolabeled liquid (for example, water mixed with technetium Tc 99m sulfur colloid or radiolabeled food), and the radioactivity in the esophagus is measured.

- Patients with esophageal motility disorders typically have delayed passage of the radiolabel from the esophagus. Motility abnormalities should therefore be suspected in patients with negative endoscopy and an abnormal transit time.

- When barium tests and HRM impedance testing are used, there is little additional value for esophageal scintigraphy.

Fig. 2 Evaluation and management of esophageal dysphagia

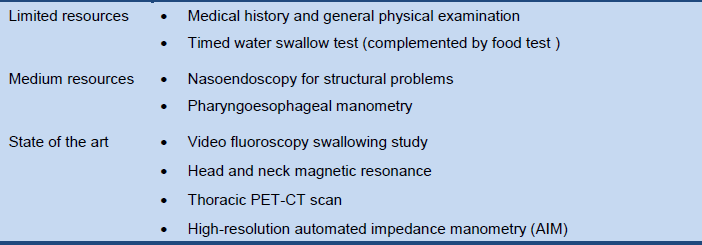

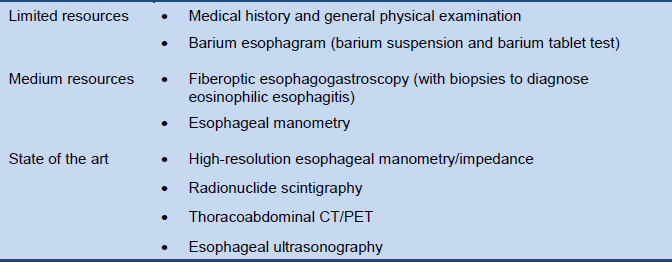

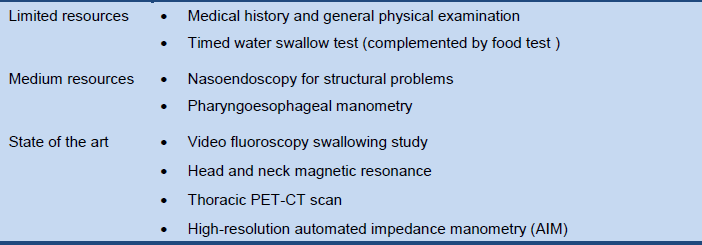

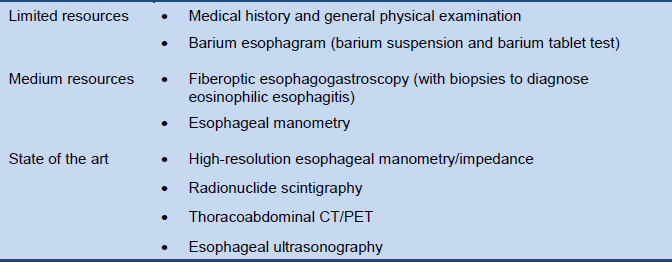

2.3 Diagnostic cascades

Tables 3 and 4 provide alternative diagnostic options for situations with limited resources, medium resources, or “state of the art” resources.

Table 3 Cascade: diagnostic options for oropharyngeal dysphagia

CT, computed tomography; PET, positron-emission tomography.

Table 4 Cascade: diagnostic options for esophageal dysphagia

CT, computed tomography; PET, positron-emission tomography.

3. Treatment options

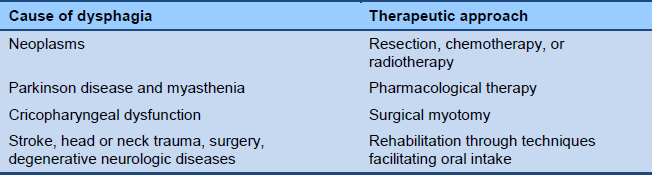

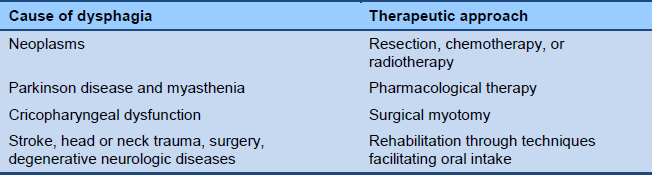

3.1 Oropharyngeal dysphagia

The goals of treatment are to improve the movement of food and drink and to prevent aspiration. The cause of the dysphagia is an important factor in the approach chosen.

Table 5 Oropharyngeal dysphagia: causes and treatment approach

The management of complications is of paramount importance. In this regard, identifying the risk of aspiration is a key element when treatment options are being considered. For patients who are undergoing active stroke rehabilitation, therapy for dysphagia should be provided to the extent tolerated. Simple remedies may be important—e.g., prosthetic teeth to fix dental problems, modifications to the texture of liquids [32] and foodstuffs [33], or a change in the bolus volume.

- Swallowing rehabilitation and reeducation:

- Appropriate postural, nutritional, and behavioral modifications can be suggested.

- Relatively simple maneuvers during swallowing may reduce oropharyngeal dysphagia.

- Specific swallowing training by a specialist in swallowing disorders.

- Various swallowing therapy techniques have been developed to improve impaired swallowing. These include strengthening exercises and biofeedback.

- Nutrition and dietary modifications:

- Softer foods, possibly in combination with postural measures, are helpful.

- Oral feeding is best whenever possible. Modifying the consistency of food to thicken fluids and providing soft foods can make an important difference [34].

- Care must be taken to monitor fluid and nutritional needs (in view of the risk of dehydration).

- Adding citric acid to food improves swallowing reflexes, possibly due to the increased gustatory and trigeminal stimulation provided by acid [35].

- Adjuvant treatment with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor to facilitate the cough reflex may also be helpful [36].

- Alternative nutritional support:

- A fine-bore soft feeding tube passed down under radiological guidance should be considered if there is a high risk of aspiration, or when oral intake does not provide adequate nutritional status.

- Gastrostomy feeding after stroke reduces the mortality rate and improves the patients’ nutritional status in comparison with nasogastric feeding.

- Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy involves passing a gastrostomy tube into the stomach via a percutaneous abdominal route under guidance from an endoscopist, and if available this is usually preferable to surgical gastrostomy.

- The probability that feeding tubes may eventually be removed is lower in patients who are elderly, have suffered a bilateral stroke, or who aspirate during the initial video fluoroscopic study [37].

- Jejunal tube feeding should be used in the acute setting, and percutaneous gastrostomy or jejunostomy tube feeding in the chronic setting.

- Surgical treatments aimed at relieving the spastic causes of dysphagia, such as cricopharyngeal myotomy, have been successful in up to 60% of cases, but their use remains controversial [38]. On the other hand, open surgery and endoscopic myotomy in patients with Zenker diverticulum is a well-established therapy.

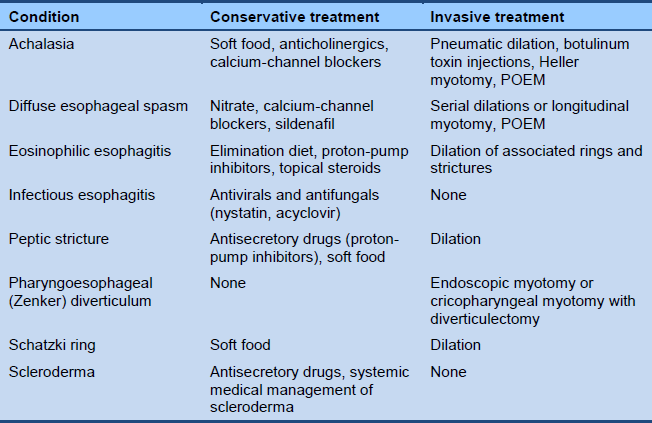

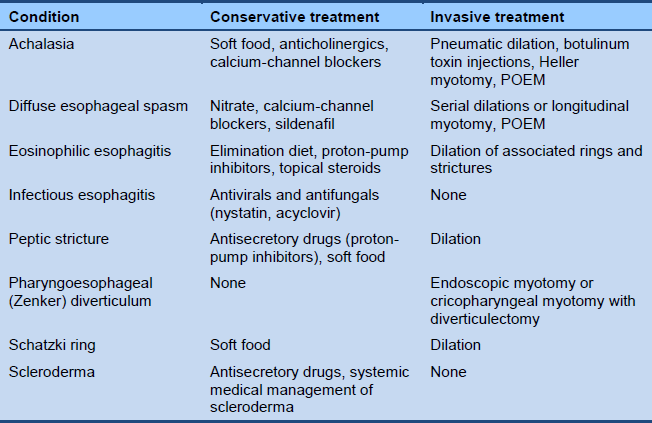

3.2 Esophageal dysphagia

Acute dysphagia requires immediate evaluation and intervention. In adults, the most common cause is food impaction. There may be an underlying component of mechanical obstruction. Immediate improvement is seen after removal of the impacted food bolus. Care should be taken to avoid the risk of perforation by pushing down the foreign body.

A list of management options for esophageal dysphagia that may be taken into consideration is provided in Table 6.

Table 6 Management options for esophageal dysphagia

POEM, peroral endoscopic myotomy.

Peptic esophageal strictures

Peptic strictures are usually the result of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), but strictures can also be caused by medication. The differential diagnosis has to exclude:

- Caustic strictures after ingestion of corrosive chemicals

- Drug-induced strictures

- Postoperative strictures

- Fungal strictures

- Eosinophilic esophagitis

When the stricture has been confirmed endoscopically, gradual dilation [39,40] with a Savary bougie is the treatment of choice. Balloon dilation is an alternative option, but it may be riskier.

- Aggressive antireflux therapy with proton-pump inhibitors—such as omeprazole 20 mg b.i.d. or equivalent—or fundoplication improves dysphagia and decreases the need for subsequent esophageal dilations in patients with peptic esophageal strictures. Higher doses may be required in some patients.

- For patients whose dysphagia persists or returns after an initial trial of dilation and antireflux therapy, healing of reflux esophagitis should be confirmed endoscopically before dilation is repeated.

- When healing of reflux esophagitis has been achieved, the need for subsequent dilations is assessed empirically.

- Patients who experience only short-lived relief of dysphagia after dilation can be taught the technique of self-bougienage.

- For refractory strictures, therapeutic options include intralesional steroid injection prior to dilation, and endoscopic electrosurgical incision.

- Rarely, truly refractory strictures require esophageal resection and reconstruction.

- Exceptionally, an endoluminal prosthesis may be indicated in patients with benign strictures [41]. The risk of perforation is about 0.5% and there is a high rate of stent migration in these conditions.

- Surgery is generally indicated if frank perforation occurs, but endoscopic methods of wound closure are being developed.

Treatment of lower esophageal mucosal rings (including Schatzki ring)

- Dilation therapy for lower esophageal mucosal rings involves the passage of a single large bougie (45–60 Fr) or balloon dilation (18–20 mm) aimed at fracturing (rather than merely stretching) the rings.

- After abrupt dilation, any associated reflux esophagitis is treated aggressively with high-dose proton-pump inhibitors.

- The need for subsequent dilations is determined empirically. However, recurrence of dysphagia is possible, and patients should be advised that repeated dilation may be needed subsequently. Esophageal mucosal biopsies should be obtained in such cases to evaluate for possible eosinophilic esophagitis.

- Esophageal manometry is recommended for patients whose dysphagia persists or returns quickly despite adequate dilation and antireflux therapy.

- For patients with a treatable motility disorder such as achalasia, therapy is directed at the motility problem.

- If a treatable motility disorder is not found, endoscopy is repeated to confirm that esophagitis has healed and that the ring has been disrupted.

- For patients with persistent rings, another trial of dilation is usually warranted.

- Refractory rings that do not respond to dilation using standard balloons and bougies may respond to endoscopic electrosurgical incision and surgical resection. These therapies should be required only rarely for patients with lower esophageal mucosal rings, and only after other causes of dysphagia have been excluded.

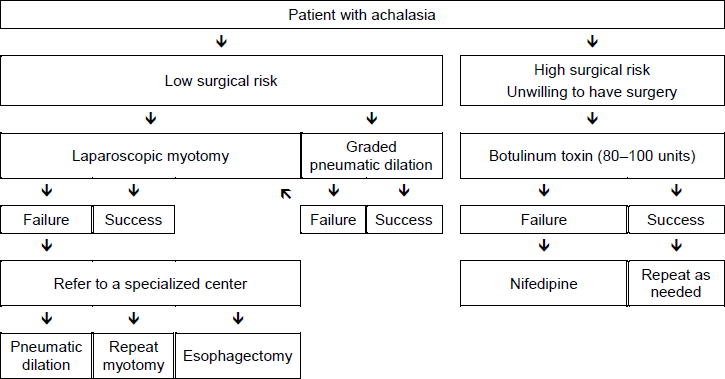

Achalasia

- The possibility of pseudoachalasia (older age, fast and severe weight loss) or Chagas disease should be excluded.

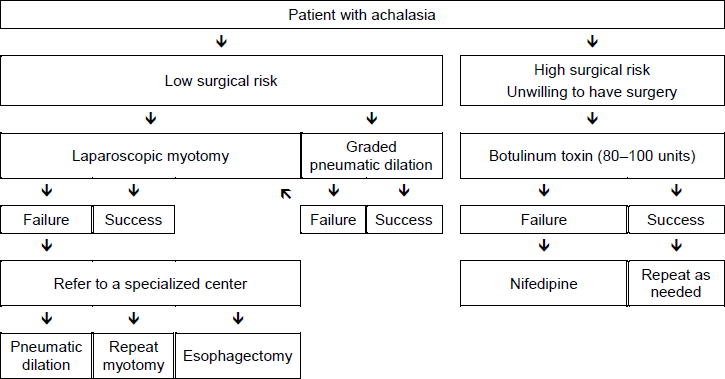

- The management of achalasia depends largely on the surgical risk.

- Medical therapy with nitrates or calcium-channel blockers is often ineffective or poorly tolerated.

- Botulinum toxin injection may be used as an initial therapy for patients who have a poor surgical risk, if the clinician considers that medications and pneumatic dilation would be poorly tolerated. Botulinum toxin injection appears to be a safe procedure that can induce a clinical remission for at least 6 months in approximately two-thirds of patients with achalasia. However, most patients will need repeated injections to maintain the remission. The long-term results with this therapy have been disappointing, and some surgeons feel that surgery is made more difficult by the scarring that may be caused by injection therapy.

- When these treatments have failed, the physician and patient must decide whether the potential benefits of pneumatic dilation or myotomy outweigh the substantial risks that these procedures pose for elderly or infirm patients.

- For those in whom surgery is an option, most gastroenterologists will start with pneumatic dilation with endoscopy and opt for laparoscopic Heller-type myotomy in patients in whom two or three graded pneumatic dilations (with 30- mm, 35-mm, and 40-mm balloons) have failed. Some gastroenterologists prefer to opt directly for surgery without a prior trial of pneumatic dilation, or limit the

- diameter of pneumatic dilators used to 30–35 mm.

- Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) is becoming available as an alternative to either pneumatic dilation or Heller myotomy.

- If these treatments fail, especially in patients with a decompensated esophagus, esophagectomy may be required.

- A feeding gastrostomy is an alternative to pneumatic dilation or myotomy, but many neurologically intact patients find that life with a gastrostomy is unacceptable.

Fig. 3 Management options in patients with achalasia

Eosinophilic esophagitis

- Eosinophilic esophagitis is an allergen-driven inflammation of the esophagus [42].

- The diagnosis is based on histological examination of mucosal biopsies from the upper and lower esophagus after initial treatment with proton-pump inhibitors for 6–8 weeks. Approximately one-third of patients with suspected eosinophilic esophagitis achieve remission with proton-pump inhibitor therapy [43].

- Identification of the underlying food or airborne allergen can direct dietary advice.

- A six-food elimination diet can be tried if specific allergens cannot be identified.

- Standard recommendations for pharmacologic therapy of eosinophilic esophagitis include topical corticosteroids and leukotriene antagonists [44,45].

- Esophageal dilation for patients with associated strictures and rings is safe (with a true perforation rate of less than 1%) and effective (with dysphagia improving for up to 1–2 years in over 90% of cases) [46,47].

3.3 Management cascades

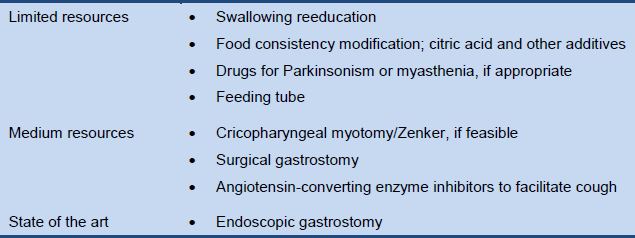

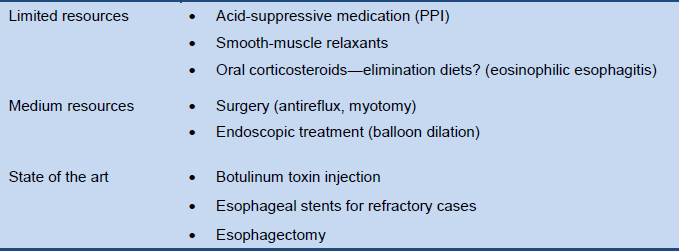

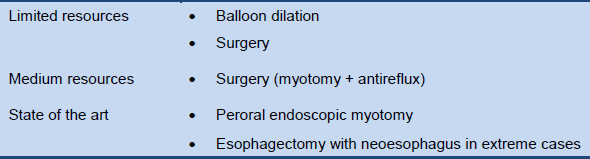

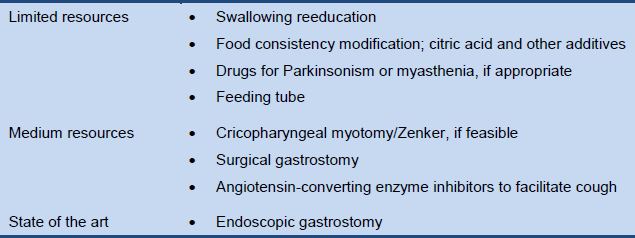

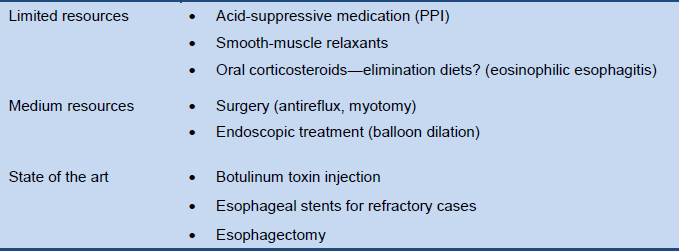

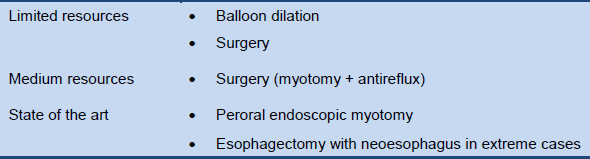

Tables 7–9 list alternative management options for situations with limited resources, medium-level resources, or “state of the art” resources.

Table 7 Cascade: management options for oropharyngeal dysphagia

Table 8 Cascade: management options for esophageal dysphagia

PPI, proton-pump inhibitor.

Table 9 Cascade: management options for achalasia

4. References

General references

Ali MA, Lam-Himlin D, Voltaggio L. Eosinophilic esophagitis: a clinical, endoscopic, and histopathologic review. Gastrointest Endosc 2012;76:1224–37.

Bohm ME, Richter JE. Review article: oesophageal dilation in adults with eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;33:748–57.

Moawad FJ, Cheatham JG, DeZee KJ. Meta-analysis: the safety and efficacy of dilation in eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;38:713–20.

Molina-Infante J, Katzka DA, Gisbert JP. Review article: proton pump inhibitor therapy for suspected eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;37:1157–64.

Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, Frei C, Bussmann C, Beglinger C, et al. Long-term budesonide maintenance treatment is partially effective for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;9:400–9.

Reference list

- Ginsberg GG. Food bolus impaction. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;3:85–6.

- Hila A, Castell D. Upper gastrointestinal disorders. In: Hazzard W, Blass J, Halter J, Ouslander J, Tinetti ME, editors. Principles of geriatric medicine and gerontology. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2003: 613–40.

- Shamburek RD, Farrar JT. Disorders of the digestive system in the elderly. N Engl J Med 1990;322:438–43.

- Hinchey JA, Shephard T, Furie K, Smith D, Wang D, Tonn S, et al. Formal dysphagia screening protocols prevent pneumonia. Stroke J Cereb Circ 2005;36:1972–6.

- Donovan NJ, Daniels SK, Edmiaston J, Weinhardt J, Summers D, Mitchell PH, et al. Dysphagia screening: state of the art: invitational conference proceeding from the State-of-the-Art Nursing Symposium, International Stroke Conference 2012. Stroke J Cereb Circ 2013;44:e24–31.

- Kalf JG, de Swart BJM, Bloem BR, Munneke M. Prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2012;18:311–5.

- Nicaretta DH, Rosso AL, Mattos JP de, Maliska C, Costa MMB. Dysphagia and sialorrhea: the relationship to Parkinson’s disease. Arq Gastroenterol 2013;50:42–9.

- Atmatzidis K, Papaziogas B, Pavlidis T, Mirelis C, Papaziogas T. Plummer–Vinson syndrome. Dis Esophagus 2003;16:154–7.

- Holland G, Jayasekeran V, Pendleton N, Horan M, Jones M, Hamdy S. Prevalence and symptom profiling of oropharyngeal dysphagia in a community dwelling of an elderly population: a selfreporting questionnaire survey. Dis Esophagus 2011;24:476–80.

- Turley R, Cohen S. Impact of voice and swallowing problems in the elderly. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2009;140:33–6.

- Lin LC, Wu SC, Chen HS, Wang TG, Chen MY. Prevalence of impaired swallowing in institutionalized older people in Taiwan. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:1118–23.

- United States. Congress. House. Resolution expressing the sense of the Congress that a National Dysphagia Awareness Month should be established. 110th Congress. 2nd session. H. Con. Res. 195 (2008). Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 2008. Available at: http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/z?c110:H.CON.RES.195:.

- Kidambi T, Toto E, Ho N, Taft T, Hirano I. Temporal trends in the relative prevalence of dysphagia etiologies from 1999–2009. World J Gastroenterol 2012;18:4335–41.

- Rutegård M, Lagergren P, Nordenstedt H, Lagergren J. Oesophageal adenocarcinoma: the new epidemic in men? Maturitas 2011;69:244–8.

- Ronkainen J, Talley NJ, Aro P, Storskrubb T, Johansson SE, Lind T, et al. Prevalence of oesophageal eosinophils and eosinophilic oesophagitis in adults: the population-based Kalixanda study. Gut 2007;56:615–20.

- Hruz P, Straumann A, Bussmann C, Heer P, Simon HU, Zwahlen M, et al. Escalating incidence of eosinophilic esophagitis: a 20-year prospective, population-based study in Olten County, Switzerland. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;128:1349–50.

- Zhang HZ, Jin GF, Shen HB. Epidemiologic differences in esophageal cancer between Asian and Western populations. Chin J Cancer 2012;31:281–6.

- Ronkainen J, Agréus L. Epidemiology of reflux symptoms and GORD. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2013;27:325–37.

- Matsuda NM, Miller SM, Evora PRB. The chronic gastrointestinal manifestations of Chagas disease. Clinics (São Paulo, Brazil) 2009;64:1219–24.

- Blackwell Z, Littlejohns P. A review of the management of dysphagia: a South African perspective. J Neurosci Nurs 2010;42:61–70.

- National Stroke Foundation. Clinical guidelines for stroke management 2010. Melbourne: National Stroke Foundation, 2010: 78–95.

- Scharitzer M, Pokieser P, Schober E, Schima W, Eisenhuber E, Stadler A, et al. Morphological findings in dynamic swallowing studies of symptomatic patients. Eur Radiol 2002;12:1139–44.

- Barkhausen J, Goyen M, von Winterfeld F, Lauenstein T, Arweiler-Harbeck D, Debatin JF. Visualization of swallowing using real-time TrueFISP MR fluoroscopy. Eur Radiol 2002;12:129–33.

- Ramsey DJC, Smithard DG, Kalra L. Early assessments of dysphagia and aspiration risk in acute stroke patients. Stroke J Cereb Circ 2003;34:1252–7.

- Pikus L, Levine MS, Yang YX, Rubesin SE, Katzka DA, Laufer I, et al. Videofluoroscopic studies of swallowing dysfunction and the relative risk of pneumonia. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003;180:1613–6.

- Perlman AL, Witthawaskul W. Real-time remote telefluoroscopic assessment of patients with dysphagia. Dysphagia 2002;17:162–7.

- Omari TI, Dejaeger E, van Beckevoort D, Goeleven A, Davidson GP, Dent J, et al. A method to objectively assess swallow function in adults with suspected aspiration. Gastroenterology 2011;140:1454–63.

- Chang YC, Chen SY, Lui LT, Wang TG, Wang TC, Hsiao TY, et al. Dysphagia in patients with nasopharyngeal cancer after radiation therapy: a videofluoroscopic swallowing study. Dysphagia 2003;18:135–43.

- Katz PO, Knuff TE, Benjamin SB, Castell DO. Abnormal esophageal pressures in reflux esophagitis: cause or effect? Am J Gastroenterol 1986;81:744–6.

- Spechler SJ. AGA technical review on treatment of patients with dysphagia caused by benign disorders of the distal esophagus. Gastroenterology 1999;117:233–54.

- Ott DJ. Radiographic techniques and efficacy in evaluating esophageal dysphagia. Dysphagia 1990;5:192–203.

- Cichero J, Nicholson T, Dodrill P. Liquid barium is not representative of infant formula: characterisation of rheological and material properties. Dysphagia 2011;26:264–71.

- Gisel E. Interventions and outcomes for children with dysphagia. Dev Disabil Res Rev 2008;14:165–73.

- Wilkinson TJ, Thomas K, MacGregor S, Tillard G, Wyles C, Sainsbury R. Tolerance of early diet textures as indicators of recovery from dysphagia after stroke. Dysphagia 2002;17:227–32.

- Pelletier CA, Lawless HT. Effect of citric acid and citric acid-sucrose mixtures on swallowing in neurogenic oropharyngeal dysphagia. Dysphagia 2003;18:231–41.

- Marik PE, Kaplan D. Aspiration pneumonia and dysphagia in the elderly. Chest 2003;124:328–36.

- Ickenstein GW, Kelly PJ, Furie KL, Ambrosi D, Rallis N, Goldstein R, et al. Predictors of feeding gastrostomy tube removal in stroke patients with dysphagia. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2003;12:169–74.

- Gervais M, Dorion D. Quality of life following surgical treatment of oculopharyngeal syndrome. J Otolaryngol 2003;32:1–5.

- Mann NS. Single dilation of symptomatic Schatzki ring with a large dilator is safe and effective. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:3448–9.

- Dumon JF, Meric B, Sivak MV, Fleischer D. A new method of esophageal dilation using Savary-Gilliard bougies. Gastrointest Endosc 1985;31:379–82.

- Pouderoux P, Verdier E, Courtial P, Bapin C, Deixonne B, Balmès JL. Relapsing cardial stenosis after laparoscopic nissen treated by esophageal stenting. Dysphagia 2003;18:218–22.

- Dellon ES. Diagnosis and management of eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:1066–78.

- Molina-Infante J, Katzka DA, Gisbert JP. Review article: proton pump inhibitor therapy for suspected eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;37:1157–64.

- Straumann A, Conus S, Degen L, Frei C, Bussmann C, Beglinger C, et al. Long-term budesonide maintenance treatment is partially effective for patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;9:400–9.

- Ali MA, Lam-Himlin D, Voltaggio L. Eosinophilic esophagitis: a clinical, endoscopic, and histopathologic review. Gastrointest Endosc 2012;76:1224–37.

- Bohm ME, Richter JE. Review article: oesophageal dilation in adults with eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;33:748–57.

- Moawad FJ, Cheatham JG, DeZee KJ. Meta-analysis: the safety and efficacy of dilation in eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;38:713–20.